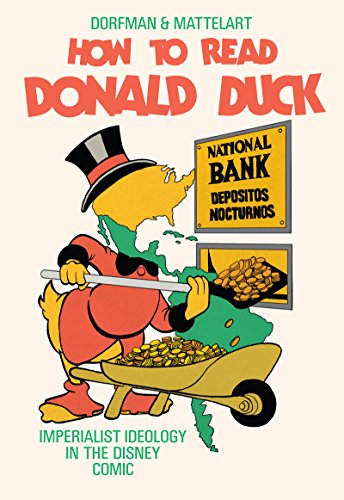

‘How to Read Donald Duck’ Returns to US Shores

Posted on May 1, 2020

Filed Under Books, Culture, Politics | Leave a Comment

It’s back.

“How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic†by Ariel Dorfman (who was the cultural adviser to President Salvador Allende from 1970 to 1973 during the short, glorious years of socialism in Chile) with the Belgian sociologist Armand Mattelart, was an instant best-seller in Chile in 1971.

The comic-book-sized publication took a political (Marxist) look at the capitalist ideological underpinnings of the Walt Disney-Donald Duck comic books and how they promulgated imperialism in Chile (and elsewhere) — not to mention the American model of consumerism, sexuality and culture. If you were (or still are) a reader of Donald’s adventures (along with his three nephews and Scrooge McDuck) you’ll recall the many trips the characters made to “backwater” third-world countries where they conivingly tried to “swindle” the “natives” out of their rices — gold, diamonds, ores and minerals, oil, and their land — only to enrich their own coffers (Scrooge loved to “swim” in his vault of billions) – or create a revolution against “bad” governments.

According to Dan Piepenbring in the New Yorker (June 3, 2019):

“The book was translated into nearly a dozen languages, including English, and sold half a million copies. But American publishing houses blanched at the prospect of a lawsuit from Disney, which was known to litigate early and often. In 1975, a small imprint agreed to a modest run of about four thousand copies. The books were printed in the U.K. and shipped to the U.S. But, when they arrived in New York, Customs impounded them, on suspicion of ‘piratical copying.’ The books reproduced panels from Disney comics without permission. Customs invited lawyers from both sides to plead their cases. Disney argued that parents might pick up the book thinking it was a bona-fide Disney publication, unwittingly delivering radical propaganda to their children. Customs ultimately sided with the authors—but, citing an obscure nineteenth-century importation clause that was intended to curb the arrival of counterfeit books from abroad, the agency admitted only a miserly fifteen hundred copies into the U.S.”

In 1973, Augusto Pinochet seized power from Allende, in a violent military coup that was underwritten by the US; under Pinochet’s rule, the book was banned, as an emblem of a fallen way of thought. Copies were burned and thrown into the ocean.

Fortunately, the First Edition of the book was republished by O/R Books in 2018 and an updated version was published by UK Pluto Books in 2018. It includes a new introduction by Ariel Dorfman in addition to the original preface to the English edition by Dorfman and Mattelart, as well as the introduction to the English edition by translator David Kunzle.

Here’s Ariel Dorfman from an article in The Guardian, Fri 5 Oct 2018:

“Probing hundreds of Disney comic strips – sold by the million on newsstands in Chile and countless other lands – we had tried to reveal the ideological messages that underlay those supposedly innocent, supposedly apolitical stories.

We wanted Chilean readers to realise they were being fed values that were inimical to a revolution that sought to unshackle them from centuries-old exploitation: competition rather than solidarity, prejudice rather than critical thinking, obedience rather than rebellion, paternalism rather than resistance, money rather than compassion as the standard of worth.

We wanted Chileans to realise they were being fed values inimical to a revolution … to understand how previous rulers had presented subjugation as normal, natural and benign

It was not enough, we felt, to change the economic and social structures that benefited a rich minority and their international corporate allies. It was also imperative to understand how the previous rulers of our land had presented this subjugation as normal, natural and benign; how they had been covertly selling us an American model of success and consumer affluence as the false solution to poverty and misdevelopment.

Just as copper and other resources usurped by foreign hands needed to be recovered for the nation, so too did our dreams and desires. We had to take back control, forge a new identity, devise new forms of entertainment. Our book was meant to contest the authoritarian plots imported from the US, to open spaces for stories of our own making.

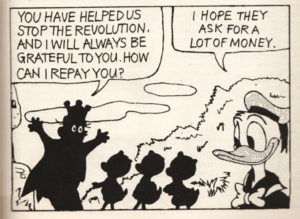

We used the Disney cartoons to suggest the aseptic, oppressive sexuality in the Duck family, the way third-world natives were depicted as savages and idiots, the way riches were never produced by workers but always by investors, and how villains were portrayed with racial bias. In this realm, female Ducks are flirtatiously worried about their beauty, yet strangely asexual (Daisy: “If you teach me to skate this afternoon, I will give you something you always wanted.†Donald: “You mean …?†Daisy: “Yes … my 1872 coin.â€) And the model jobs for the Duck nephews when playing a game at school about the adults they want to become: “I’d like to be a banker!†says Dewey, echoed by Huey: “I’ll pretend I’m a big landlord with lots of land to sell.†Or take the witch doctor who brags about his nation being modern because “Gottee telephone. Only trouble is only one has wires. It’s a hot line to the World Loan Bank.â€

For further reading:

Comments

Leave a Reply